I’ve just finished watching the Netflix drama series Ripley, an adaptation of Patricia Highsmith’s novel The Talented Mr Ripley. I’ll leave the full reviews to the pros, but I particularly loved how the show evoked the early-60s era: messages left at hotel desks, language courses on vinyl records, and how, if you wanted to track someone down, you couldn’t just stalk them on social media like we do now; you had to hire a private detective. Ripley’s pacing, wardrobes and sumptuous black-and-white cinematography only added to the sense of being transported back in time.

And how can I not mention the actual writing of letters for communication? There was even a scene in which the main character Tom Ripley, played by Andrew Scott, was seen to buy a stamp and stick it on an envelope!

It’s a real credit to the show that I was enjoying it so much, I didn’t even pause it to check that they were using period-accurate stamps and postage rates. Try it sometime! People watching won’t be annoyed at all, in fact they will thank you for your devotion to accuracy.

Fortunately, fans of postal history don’t need production designers to transport us into the past. Real-life mail is a window into lives, attitudes and actions from another era.

I love poking around an old envelope or, if I’m really lucky, the letter inside, and researching the individuals involved. Every item is a time capsule of its age, and all the more intriguing because it was there. You’re holding a letter that once passed through the actual hands of the people whose lives you can now explore.

This tangible connection with history is highly valued by many collectors, but sadly, it’s little appreciated by those outside the craft. It’s very easy to explain, when you get the chance – who doesn’t like reading other people’s mail? – but the world still thinks of us as list-checkers and box-tickers instead of the cultural archivists/historical stickybeaks that we really are.

Recently I took time out from hardly ever updating this blog to do some actual collecting. One moment I was sifting through some stray items in a box of junk; the next, I was enmeshed in the political, artistic and literary circles of early 20th-century Australia.

I’d picked up the small, flat box at a club auction for next to nothing because it contained a few stamp booklets of interest, and some fresh sticky notes that would have cost more in a shop than what I had paid. There’s a win already!

But the real fun often comes from the stuff we don’t want, and this box was mostly postcards. Postcards are so hot right now, I’m surprised I didn’t have more competition at the auction. Perhaps it was because most of them were modern, and a little dull.

…But not all of them. I picked up one postcard that called for a little research, and while some answers were quick to come by, I found that each discovery triggered more curiosity. The result was a fascinating wander through a bygone era. I got to bed that night much later than I’d meant to.

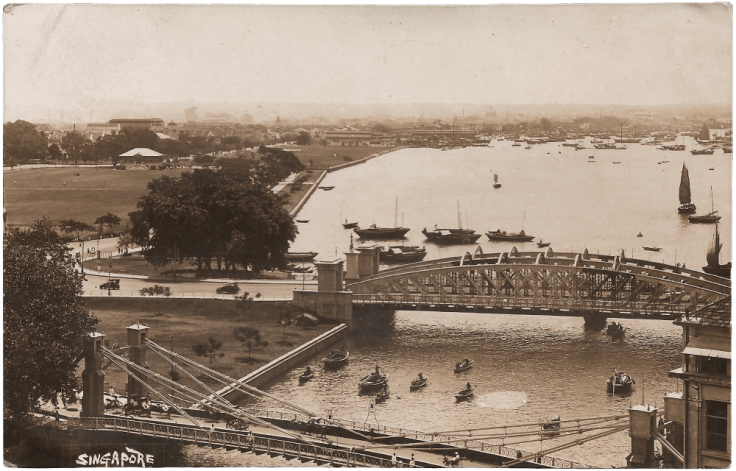

To Norman, from Singapore

The postcard that caught my eye was sent to Melbourne from Singapore in August 1927, when the island colony was still one of Britain’s ‘Straits Settlements’. In the centre of the photo, two cars have just driven across the Singapore River via the Anderson Bridge. Boats sit at anchor in the background, and if you look closely at the foreground, you can see passengers being hauled over the Cavenagh Bridge on rickshaws.

The postcard was addressed to ‘Norman Lilley Esq.’, care of the office of the Argus.

The Argus was a big Melbourne newspaper in those days, so naturally I wondered who Norman Lilley was. Luckily, Norman left a big enough cultural footprint that I was quickly able to trace him, despite his complete lack of a Facebook page.

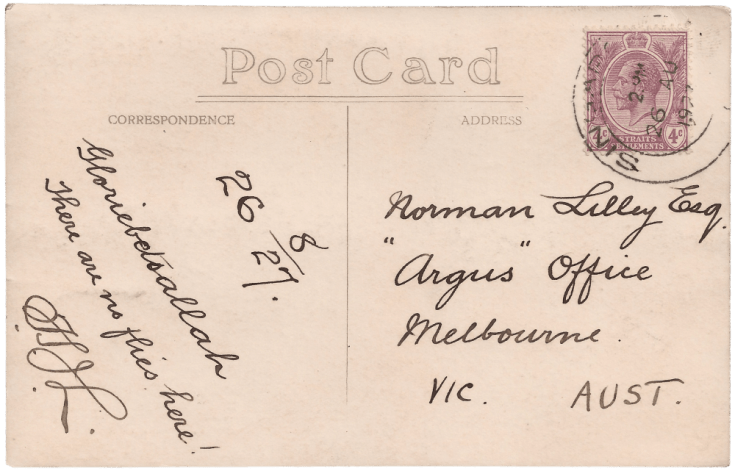

Norman was a newspaper typesetter at the Argus who made his way from the compositing room into journalism. He moved to Sydney, where his passion for literature saw him editing the literary page for a union newspaper, the Australian Worker. He also founded Lilley’s Magazine in 1911 to showcase Australian writing.

It seems the magazine didn’t last long, and in 1916 Norman returned to an editorial job back at the Argus. He died in 1941, and there’s a whole collection of his papers at the State Library of New South Wales that this postcard seems to have evaded. Norman himself seems to have evaded cameras, because this was the only image I could find of him on the entire internet:

But the benefit of hanging out with writers is that even if there are no decent photographs of you, someone will at least have written some nice words. As Norman departed the Worker to return to Melbourne, poet R. J. Cassidy’s tribute read, in part:

“He can see the filth of the earth in the delicate tints and textures of the butterfly’s wing; he can see beauty beyond compare in the foetid slime of the gutter wherein the worms and maggots crawl.”

My new ambition in life is to ensure that whoever gives the eulogy at my funeral, they will feel obliged to mention the foetid slime of the gutter.

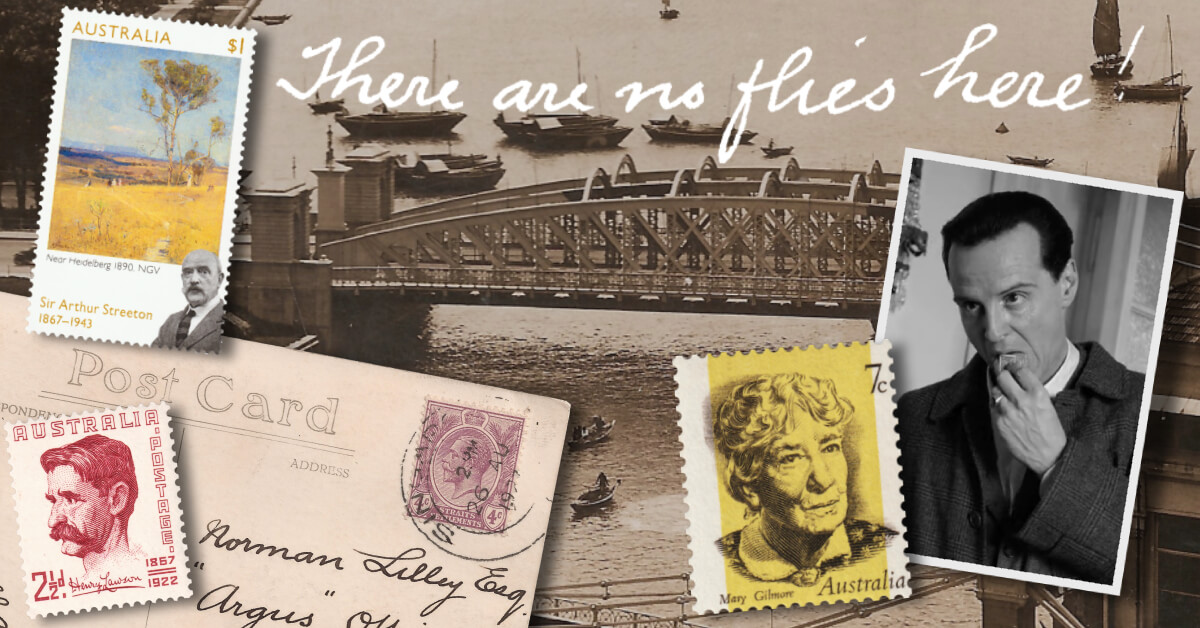

Noman Lilley’s name turned up in some quite modern Internet hits: his review of a 1932 exhibition by the artist Sir Arthur Streeton is still cited at auctions of Streeton’s paintings today. You might have some Streeton works in your own collection. Not your art collection. Your stamp collection.

OK, so now I knew who got the postcard. But who sent it? This was going to require some real research.

In search of HJL

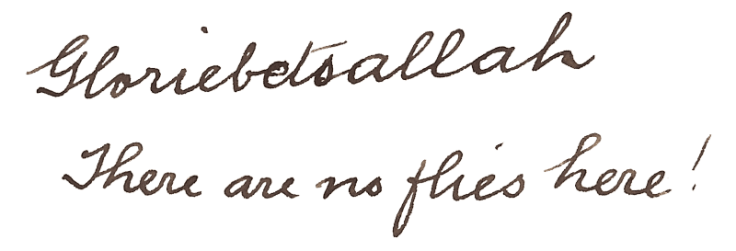

The brevity and informality of the message suggests a close friend or relative:

Gloriebetoallah [sic]

There are no flies here!

HJL

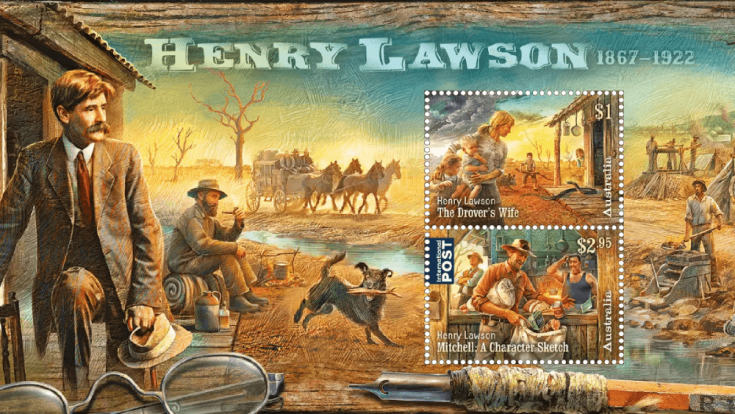

I had to wonder: knowing Norman Lilley’s literary circles, could ‘HJL’ have been the much-admired Australian poet Henry Lawson? I knew a bit about Lawson’s life, but I didn’t remember a visit to Singapore being depicted on the 2017 minisheet.

Alas, I soon found out that Lawson’s initials were HAHL, for ‘Henry Archibald Hertzberg Lawson’. You learn something every day. And making it even more unlikely that Lawson would be sending a postcard from Singapore in 1927 was the fact that he had died in 1922. (Source: the top of the minisheet.)

Failing to find any other candidates, I nervously embarked on a first for my philatelic research career: I asked ChatGPT for help. You may know ChatGPT, it’s one of those artificial intelligence chatbots that are currently assisting society almost as rapidly as they are destroying it.

I asked ChatGPT to suggest Australian literary figures of the era with the initials ‘HJL’, and didn’t I feel smug when its first suggestion was ‘Henry Lawson’? Nice to know that billions of investment dollars and zillions of algorithmic calculations led an AI giant to the same incorrect answer that my brain came up with all on its own.

(Of course ChatGPT suggested a bloke with the wrong initials. If ChatGPT doesn’t know something, it just goes ahead and draws entirely incorrect conclusions, and declares its findings as fact. I once asked it what my best work was, and it said very nice things about my writing on a TV show that I had nothing to do with.)

ChatGPT’s next suggestion was “Hector Julius Lamond.” ‘Julius’ was probably just ChatGPT taking guesses again… but could there have been a ‘Hector Lamond’?

It turns out, yes. Hector Lamond was another journalist and literary figure of the day – and the editor of the Australian Worker at the time of Norman Lilley’s employment there. Bingo!

The Lone Hand magazine, June 1914

Well OK, I can’t say for certain that ‘HJW’ from the postcard was Hector Lamond, but he’s got to be our prime suspect (more circumstantial evidence to come).

I also doubt that his middle name was ‘Julius’; he worked with a guy called ‘Harry Julius’ at one stage, and that’s probably enough evidence for ChatGPT to smoosh them together and decide they were one person. I haven’t actually been able to unearth any middle name for Hector: from the registration of his birth to the location of his scattered ashes, he only ever shows up as Hector “One-Given-Name” Lamond.

The gang’s all here

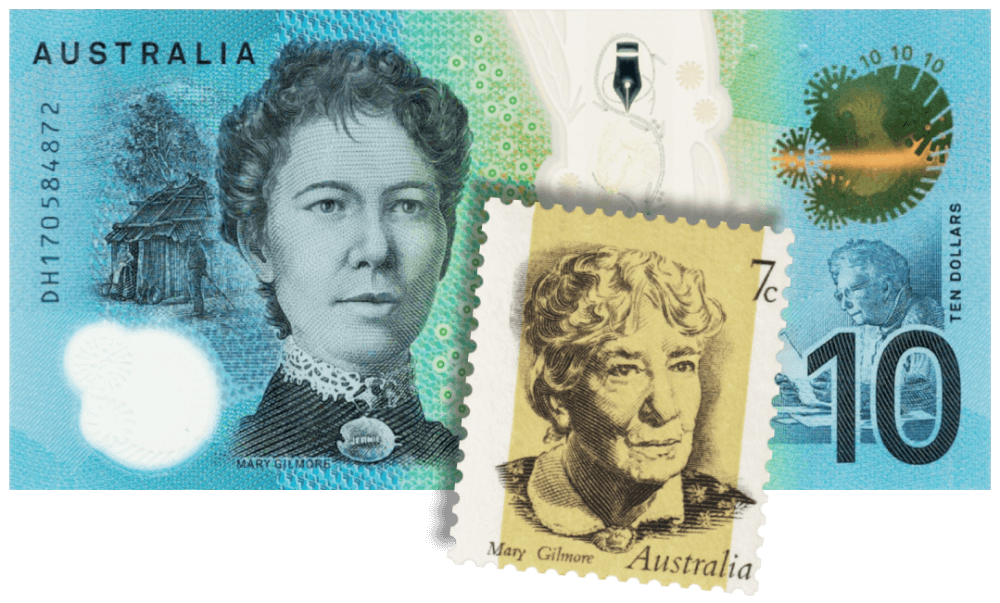

Even if the postcard writer wasn’t our Hector, by this point I was just enjoying the journey. The tangents kept luring me away. For example, it was during Lamond’s tenure at the Worker that the writer and social activist Mary Gilmore requested a women’s column; Lamond suggested she edit it, so she did, from 1908 until 1931. It became the paper’s best-known column.

Mary campaigned for a wide range of reforms – the vote for women, relief from poverty, old-age pensions, fair treatment for Aboriginal Australians – that are taken for granted now. That would be why she got a stamp in 1973, and why she’s on the Australian ten-dollar note these days.

At Mary Gilmore’s death in 1962, she was given the first state funeral since that of another Australian writer with whom she had once had something of an all-fated relationship: none other than… Henry “not that guy” Lawson!

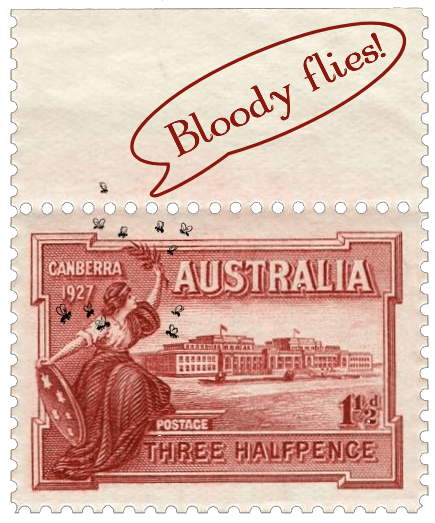

Back to Hector Lamond, and he left the Worker in 1916 during a bitter debate over World War I conscription among the political left. He wound up in Australia’s Federal Parliament, where he served as a minister, and was involved with the development of the new national capital at Canberra.

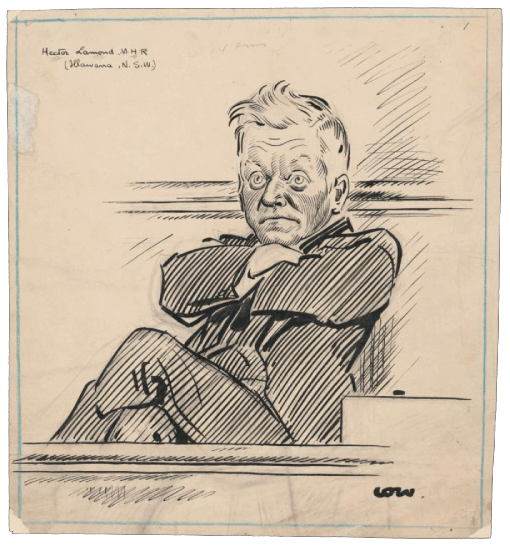

At this point, my investigations took an unexpected detour. I learned that during his Parliamentary career, Hector was caricatured by David Low, a cartoonist from New Zealand who eventually went to the UK, where he came to be considered one of the greatest political cartoonists ever. He created the pompous Colonel Blimp; you might not know the Colonel himself, but he influenced satirical depictions of pompous British army officers ever since.

National Library of Australia

Not just one to draw literal pictures, David Low drew quite a verbal image of Hector Lamond in his autobiography.

“Hector, pink of face and wild of eye, was a fanatic with the tenacity of a bulldog with a mouthful of trouser-leg when his passions were aroused. Yet tears would start down his cheek when he sat on our sofa, full of my mother’s soup, listening to my sister mournfully singing a saccharine ditty like ‘Little Grey Home in the West’.”

After the voters ended Hector’s parliamentary career in 1922, he purchased four regional newspapers, running them from the town of Bowral in New South Wales.

I’m yet to find any evidence he was travelling abroad in 1927. Yet there’s one more piece of circumstantial evidence in favour of our postcard writer being Hector Lamond. Cue a dramatic sting!

Dung dung dung!

Let’s read the postcard again:

The expansion of European agricultural practices across the Australian continent involved poo. Lots of poo, dropped by lots of sheep and cattle. Stay with me, I’m going somewhere with this.

All over the world, dung beetles process animal dung and return its nutrients to the soil, but Australia’s native dung beetles only worked with the native animal poo. They flat-out refused to touch the imported European livestock dung. It sat around fouling up the land, and became the perfect breeding ground for blowflies. They hung thick in the air; Australia’s proud new capital, Canberra, was surrounded by farmland, and was notoriously flyblown.

It wasn’t until the 1960s that imported dung beetles were very carefully released to deal with the poo problem. That program, thankfully, has been a remarkable success, and while flies still exist, they’re just not the problem they used to be.

Given that history, it makes a LOT of sense to me that, if someone – let’s say perhaps the owner of some newspapers in regional New South Wales who had been heavily involved in establishing a notoriously fly-blown national capital – travelled to Singapore in 1927, and discovered that it had no flies, well… I can understand why they would have absolutely felt that it was something worth writing home about.

(Then again, from what we learned about Norman Lilley, he might not have been impressed by Singapore’s pest-free environs. He LIKES the foetid slime of the gutter wherein the worms and maggots crawl!)

Back in Australia – if he ever left, that is – Hector Lamond popped up again in 1934, suggesting that the spelling of Canberra be changed to ‘Kanbra’, which he argued would be a more accurate phonetic representation. Apparently ‘Canberra’ was being pronounced in many different ways, which is a strange thing to read in 2025 when you’ve grown up never hearing it pronounced in any other way.

Wrote Hector:

“… There is a dignity and certainty about the phonetic spelling, Kanbra, that can never be attained by a word commencing with C and, moreover, a saving of a fourth of the letters in a word that will be used many millions of times in future years.”

Having been forced to type ‘Canberra’ six times so far in this article alone, I salute Hector’s vision. He could have saved me twelve keystrokes. My gift to you for reading this far down is that I didn’t learn this in any biographical source about the man. I discovered it myself in an archived newspaper. It’s a Punk Philatelist exclusive! You read it here first! (Unless you’ve also read the letters to the editor of the Sydney Morning Herald in 1934.)

Hector Lamond carried on editing his newspapers until his death in 1947. Canberra remains spelled ‘Canberra’ to this day. I didn’t come across any biographical book covering Hector’s life, though I saw him pop up very regularly in the biography of another writer. Would you like to take a guess who? That’s right, Henry ‘Whack-A-Mole’ Lawson! A man who died five years before this postcard was sent, but has somehow now earned himself three mentions in this write-up.

So there you have it: how my exploration of a brief exchange between two largely forgotten historical figures roamed through literature and politics, pulling in one of this nation’s greatest artists and one of her greatest social reformers, with a guest cameo by one of the world’s greatest cartoonists, with drive-by facts learned about Canberra, Henry Lawson, and cow poo. And it all started with a barely one-line postcard from a century ago.

But guess what? My night was not yet over! There was a second intriguing postcard in the box. It didn’t lead me on quite such a ride, but once again, it drew me into a literary world of the past, and left me with a mystery that I’m hoping someone out there might be able to help solve! You can read all about it my next post. Make sure to hit Subscribe if you haven’t already.

If you have enjoyed this deep dive into social philately, check out @Stampden (aka Peter) on X (aka Twitter). He researches the backgrounds of the people connected to postal articles and it’s fascinating. I also like the account ‘Postcard from the Past’ (found at @PastPostcard) which does virtually no deep-diving into senders’ or recipients’ backgrounds; it’s sometimes just hilarious to read selected quotes from historical postcards without any context.

I’ll be back again soon!

Follow me on Bluesky, Facebook, Instagram, and Threads.

Despite my recommendations above, I’m no longer regularly active on ‘X’.

REFERENCES

Norman Lilley, ‘Mr. Streeton’s Mastery: Bush, Sea and Flowers. Work of Charm Exhibited.’, The Argus, Melbourne, 31 March 1932, p8

Arthur Streeton (1867-1943), Ramparts Face the Ocean (1932), Leonard Joel Auctions, August 25, 2025

Arthur Streeton (1867-1943), Romance in Blue and Gold (1932), Smith & Singer, 16 November 2022

R. J. Cassidy, ‘Norman Lilley’, The Australian Worker, Sydney, 6 Jul 1916, p19

‘Obituary: Mr Norman Lilley’, The Argus, Melbourne, 12 August 1941, p3

The Australian Worker, National Library of Australia

Lilley’s Magazine, National Library of Australia

Clem Gorman (ed.), The Larrikin Streak: Australian Writers Look at the Legend, Pan Macmillan Publishers Australia (1990), p89

The Australian Worker, Wikipedia

Coral Lansbury, Hector Lamond (1865–1947), Australian Dictionary of Biography

The Early Years of the Worker, AWU

Mary Gilmore, Australian Schools Portrait Project

Dame Mary Gilmore, Reserve Bank of Australia

Hector Lamond, M.H.R., Illawarra, N.S.W. / David Low, National Library of Australia, PIC Drawer 8958 #R8431

David Low, Low’s Autobiography, Simon and Schuster, New York, 1957

The Lone Hand, New Series Vol. 2 No. 7, June 1914

Dung Beetle Program, CSIRO

Hector Lamond, ‘The Name of Canberra’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 15 February 1934, p5

© Philatelic product images remain the copyright of issuing postal administrations and successor authorities

Discover more from Punk Philatelist

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Gerard Hi Michael Dodd of cddstamps here just two things Brilliant piece really enjoyed reading it. Excellent work.

Second I think it would make a rather good piece for the IPDA Journal.. The Internet Philatelic Dealers Association 9 you may recall I am the General Secretary)

With your permission please can I offer it to the editor? Next issue is March – we publish every 2 months now

Best wishes great to see you back writing

Michael ( Laoag Philippines)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Michael! Thanks for the kind words. Please do offer it to the IPDA Journal editor. I’ll get in touch with you via email because I had something else to ask you!

LikeLike

look forward to hearing from you

LikeLike